|

View: 4383|Reply: 4

|

Magical Things About Sahara

[Copy link]

|

|

|

Post Last Edit by dauswq at 23-7-2010 13:11

1. SAHARAN GROUND ZERO

Analyses suggest this 45-meter-wide crater in southwestern Egypt, first spotted on Google Earth late in 2008, probably was formed in the last 5,000 years. Credit: National Museum of the Antarctic, University of Siena

Hole from on high

Researchers poring over Google Earth images have discovered one of Earth’s freshest impact craters — a 45-meter-wide pock in southwestern Egypt that probably was excavated by a fast-moving iron meteorite no more than a few thousand years ago.

Although the crater was first noticed in autumn 2008, researchers have since spotted the blemish on satellite images taken as far back as 1972, says Luigi Folco, a cosmochemist at the University of Siena in Italy. He and his colleagues report their find online July 22 in Science.

The rim of the Egyptian crater stands about 3 meters above the surrounding plain, which is partially covered with distinct swaths of light-colored material blasted from the crater by the impact. These rays, which emanate from the impact site like spokes from the hub of a wheel, are what drew researchers’ attention to the crater, says Folco. While such “rayed craters” are common on the moon and other airless bodies of the solar system, they are exceedingly rare on Earth because erosion and other geological processes quickly erase such evidence.

During expeditions to the site early in 2009 and again this year, scientists found more than 5,000 iron meteorites that together weigh more than 1.7 tons. The team estimates that the original lump of iron weighed between 5 and 10 metric tons when it slammed into the ground at a speed of around 3.5 kilometers per second, with most of the material vaporizing during the collision.

Analyses of soil samples from the site and of sand fused into glass by the impact’s intense heat and pressure may help the team estimate when the event occurred. Preliminary analyses suggest that it happened sometime during the last 10,000 years, probably no more than 5,000 years ago, Folco says. |

Rate

-

1

View Rating Log

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Post Last Edit by dauswq at 23-7-2010 12:58

2. SAHARAN BULLEYE

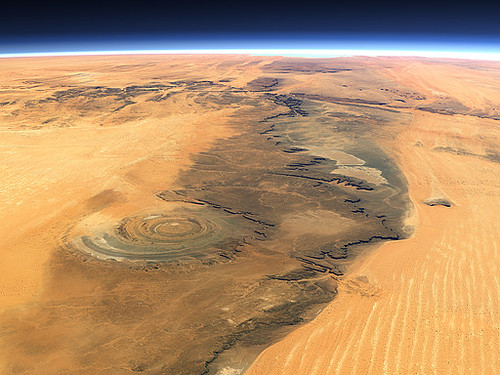

The Richat Structure: The Eyes of The Earth

Spectacular formation remains a puzzle

The Richat Structure, Oudane, Mauritania, is not really a structure but a huge circular formation (50 km in diameter - 30 miles), that resembles an eye when looked upon from space. Originally thought to be a crater, this volcanic dome is most likely a product of erosion, an ancient geological artifact in the middle of featureless Maur Adrar desert, in Africa's Western Sahara. The earliest space missions used it as a landmark, the adventurous 4x4 enthusiasts consider it to be their playground, and scientists are still debating its origin.

The Google Maps coordinates are 21.124217, -11.395569

We even found some Photoshop of this eye, combining it into an Optimus Prime-like face:

(image credit: Lebovski)

The meteorite impact theory could not explain the flatness of the "crater"'s floor, so the most accepted explanation is the erosion of the initial volcanic dome, which gradually peeled away the layers of rock, creating the present onion-like form.

This image was taken by an Expedition 15 crew member on the International Space Station. (via Space.com)

The following picture must have simulated color, for it looks almost like a fantastic lake:

(image credit: United States Geological Survey - USGS)

"Paleozoic quartzites form the resistant beds outlining the structure." (GSA Journals) A couple of other simulated images to illustrate that:

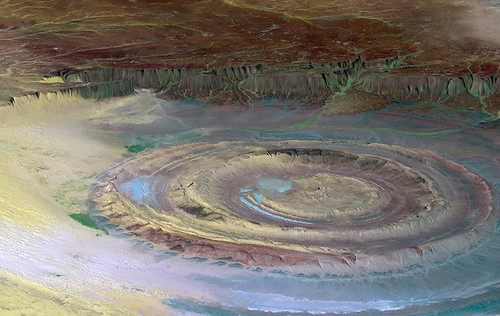

The topographical 3-D relief image, found on Wikipedia, shows "Le Guelb ri Richat" in most detail (The view is exaggerated six times vertically, the colors are slightly enhanced):

Here is a portion of this visualization, looking like landscape on some other planet:

Credit: NASA/JPL/NIMA

Johnnie Shannon image-enhanced the satellite image, clearly showing an eroded circular anticline (structural dome) of layered sedimentary rocks:

and Christoph Hormann created a spectacular view, using various modeling software:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Post Last Edit by dauswq at 23-7-2010 13:31

The man who figured out how deserts work

Among the many things that are intoxicating about the desert, the things that draw us back, I find the silence perhaps the most compelling. In a world where noise bombardment is the norm, the complete absence of sound is a shock and a fascination, the auditory equivalent of turning off your headlamp deep underground and experiencing, literally, a complete inability to see your hand held up in front of your face. Sit in the desert in the morning or at night and you can sense yourself straining to detect a sound, any sound - but there is nothing. Wilfred Thesiger, one of the great desert explorers and writers, wrote of "a silence in which only the winds played, and a cleanness that was infinitely remote from the world of men." It is only the wind that breaks the silence, gently and subtly as the day warms up and the air is on the move, sometimes expressing itself with the fury of a sandstorm. Watching the first breaths of wind gather momentum and begin their game with the sand is hypnotizing - at first a few tumbling grains, then more, gathering themselves into swirling, shape-shifting, fluid sheets dancing over the desert surface. This is the desert at work, the wind is the engine and the sculptor, and, as Thesiger observed, the only thing that breaks the silence.

We can wonder at the glorious diversity of the results of the engine's efforts - ripples, ridges, dunes in all their variety, sand seas, sandstorms, sand blasting - but our understanding of how the engine works is owed to one man, Ralph Bagnold.

Born in 1896, Bagnold was one of those extraordinary people whose skills became renowned in entirely different fields of endeavor - in his case, a military and a scientific career, united only by sand. Having survived the First World War, he was posted to Egypt in 1926 and arrived in time to watch the Great Sphinx being disinterred from its sand tomb. For a soldier in Egypt, R&R time offered many opportunities, but for Bagnold it was a chance to explore the desert - not on foot or by camel, but in Model T Fords (somewhat modified), and, later, Model A's. He pioneered the means for extended automobile expeditions, desert navigation, and driving across sand - including the giant dunes of the Great Sand Sea. As a civilian in the late 1920s and early 1930s, he accomplished journeys that no-one had thought possible, and, along the way, became fascinated by what we didn't know about the desert:

“In 1929 and 1930, during my weeks of travel over the lifeless sand sea in North Africa, I became fascinated by the vast scale of organization of the dunes and how a strong wind could cause the whole dune surface to flow, scouring sand from under one’s feet. Here, where there existed no animals, vegetation or rain to interfere with sand movements, the dunes seemed to behave like living things. How was it that they kept their precise shape while marching interminably downwind? How was it they insisted on repairing any damage done to their individual shapes? How, in other regions of the same desert, were they able to breed “babies”, just like themselves that proceeded to run on ahead of their parents? Why did they absorb nourishment and continue to grow instead of allowing the sand to spread out evenly over the desert as finer dust grains do? More basically, what kind of upward physical force must be exerted on the mineral grains to make them rise against the force of gravity, lifting them to such a height that they can strike one’s face like little hammers? No satisfactory answers to these questions existed. Indeed, no-one had investigated the physics of blown sand. So here was a new field, I thought, one that could be explored at home in England under laboratory-controlled conditions.”

And explore under laboratory-controlled conditions is exactly what he did. He was a highly-skilled engineer and designed and built his own wind tunnels and delicate measuring apparatus from scratch. He meticulously measured sand, its ranges of grain sizes and how they influenced (and were influenced by) transportation by his laboratory winds. He documented saltation, the process by which flying sand grains land and kick yet more grains into the air, and demonstrated that this is the main way in which desert sand moves, quantifying the physics and the aerodynamics. In 1938, he returned to the Sahara as a leader of a multi-disciplined expedition to the Gilf Kebir in the southwesternmost corner of Egypt, an area he and his colleagues had explored earlier. His aim was to take field measurements of moving sand and dune dynamics to test his laboratory results, an aim he accomplished with dramatic success. This was the first time that the desert's engine had been scientifically measured and documented - many questions remain today, but the basis was set out by Bagnold.

A couple of years ago, I was lucky enough to be invited to join an expedition retracing, as far as we could, Bagnold's 1938 itinerary - I was the sort of token geologist. And what an extraordinary experience that was - I became completely hooked on the desert. A visit to the site of his base camp revealed the extent to which his much-studied dune had overridden the scene. Challenges of logistics, navigation and vehicle travel in 2007 only emphasized how extraordinary had been Bagnold's achievements nearly eighty years previously.

The Second World War saw Ralph Bagnold back in his military role. Exploiting his desert expertise, he established the legendary Long Range Desert Group, a highly mobile raiding force that wrought havoc by appearing out of nowhere behind enemy lines after journeys that were thought impossible. After the war, he returned to refining and compiling his work on desert sand, the result being The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes, a work which remains a classic reference today. He later published with Carl Sagan on the sands of Mars and provided advice to NASA in preparations for the first mission to the Red Planet. And, having exhausted what could be done at the time on windblown sand without reliable long term wind data, now Brigadier Bagnold turned his attention to revolutionizing our understanding of sand transport by rivers and waves.

There is much to say about Ralph Bagnold, and I shall say more in later posts. But for now to conclude with a return to the engine, the desert wind.... I took Bagnold's writing with me through the Gilf Kebir and across the Great Sand Sea - an inspiration in an inspirational landscape, not just the science and the observations, but the resonance of his palpable love of the desert. I watched sand on the move, skittering across the desert floor under a gathering wind, avalanching spontaneously down the steep slope of a dune - and hurtling chaotically, viciously in a raging sandstorm. We had experienced minor sandstorms already, but the one that hit us in the White Desert was a monster. I have just now opened my notebook from that evening, scribbled in pencil because a pen became instantly non-functional, and some sand grains fell from between the pages. As I was blasted by the onslaught of flying sand, I felt a resonance with Ralph Bagnold who had written:

"A dense, stinging fog of low-flying sand grains wholly obscured not only our cars but ourselves up to our shoulders, while our heads stuck out against a clear blue sky. One after the other, our feet dropped an inch as sand was scoured from beneath.

The whole landscape was on the move."

On this occasion, my head did not stick out above the sand and there was no blue sky visible - until the following, incredible, morning which revealed "a cleanness that was infinitely remote from the world of men."

credit to throughthesandglass.typepad.com

The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes

The Bagnold formula, named after Ralph Alger Bagnold, relates the amount of sand moved by the wind to wind speed by saltation. It states that the mass transport of sand is proportional to the third power of the friction velocity. Under steady conditions, this implies that mass transport is proportional to the third power of the excess of the wind speed (at any fixed height over the sand surface) over the minimum wind speed that is able to activate and sustain a continuous flow of sand grains.

The formula was derived by Bagnold in 1936 and later published in his book The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes

in 1941. Wind tunnel and field experiments suggest that the formula is basically correct. It has later been modified by several researchers, but is still considered to be the benchmark formula.

In its simplest form, Bagnold's formula may be expressed as:

In its simplest form, Bagnold's formula may be expressed as:

where q represents the mass transport of sand across a lane of unit width; C is a dimensionless constant of order unity that depends on the sand sorting; ρ is the density of air; g is the local gravitational acceleration; d is the reference grain size for the sand; D is the nearly uniform grain size originally used in Bagnold's experiments (250 micrometres); and, finally, u * is friction velocity proportional to the square root of the shear stress between the wind and the sheet of moving sand.

The formula is valid in dry (desert) conditions. The effects of sand moisture at play in most coastal dunes, therefore, are not included.

For additional info: http://chinacat.coastal.udel.edu/papers/zhao-kirby-waves05.pdf |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Category: Belia & Informasi

|